There are special cars, and then there are the ones that warp your idea of reality; the cars you’ll never see outside a museum, let alone idling at a fuel station. I can count on one hand how many times I’ve found myself in this situation, but I think this particular occasion might forever remain number one.

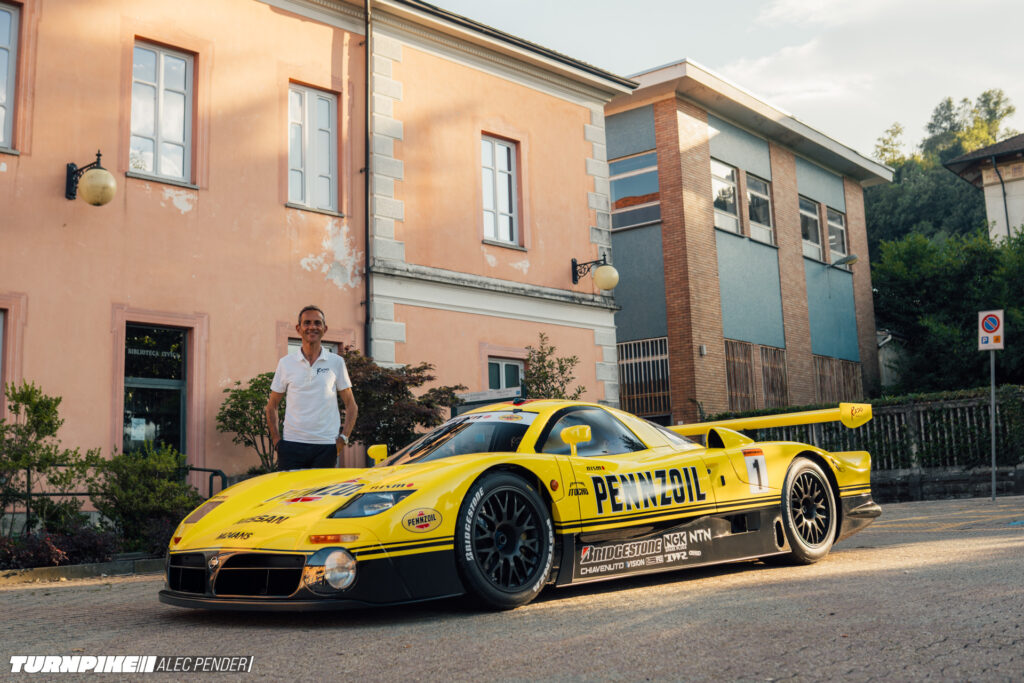

You join us in Italy, in the shadow of the Alps, with Érik Comas and his Nissan R390 GT1 – the same model he raced at Le Mans in 1998 – now restored, converted, and registered for the road. It’s a car that still looks like it’s waiting for the chequered flag, wearing Pennzoil colours that instantly send you back to late ’90s JGTC VHS tapes and championship highlights.

However that Pennzoil livery is not one that Comas used to race with, but a homage to another well known series he found success in…

If you’re even remotely into Nissan’s racing history, you likely know who Érik Comas is. In Japan, his name is permanently tied to the Pennzoil sponsored NISMO era, winning the 1998 All-Japan Grand Touring Car Championship in the R33 GT-R, then repeating it in 1999 in the R34’s debut year.

That second title is the one that cements a driver in enthusiasts’ memories forever. For a lot of people, that success is the beginning of their racing story, but not for Erik.

Comas’ career stretches way back, winning in Formula 3000 in 1990, then moving into Formula 1 and living through a period of the sport held together with bravery and luck. Comas speaks openly about the 1992 Belgian GP accident, where he was unconscious in the car, throttle pinned, engine bouncing off the limiter. None other than Ayrton Senna stopped to run over, switch the engine off, and hold Erik’s head upright until help arrived.

He’ll tell you straight, he owes his life to Senna. And it was witnessing Imola in 1994 that made him leave F1 for good, stepping away over safety concerns. Japanese motorsport came next, first with two years competing in a Toyota Supra. Then in late ’96, NISMO came knocking. This is where the R390 story gets interesting.

Comas told us that when NISMO approached him to switch from Toyota to the Skyline GT-R for the GT championship, they also used Le Mans as part of the pitch. GT1 was the new obsession then, and when Comas saw early images of the R390 project in late 1996, he instantly fell in love. He agreed to switch, but with one condition: he wanted one of the 25 homologation cars as part of the deal. Erik’s dream was simple, to own a road going GT1.

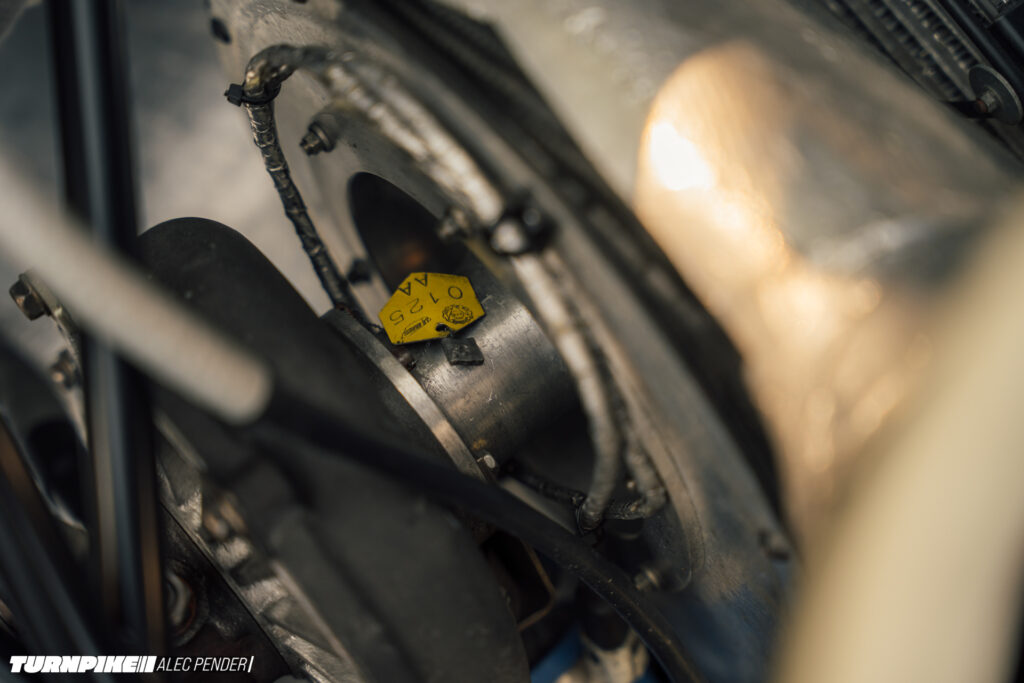

Then, the regulations shifted. For teams focusing only on Le Mans rather than a full championship, the “25 road cars” requirement was discounted, as a single homologation car would be enough. Nissan’s take on the matter was simple: we have to keep the car.

Comas’ dream was on hold. Not dead, just delayed by 20 years, at which point he approached his former employer, reminding them about their former agreement.

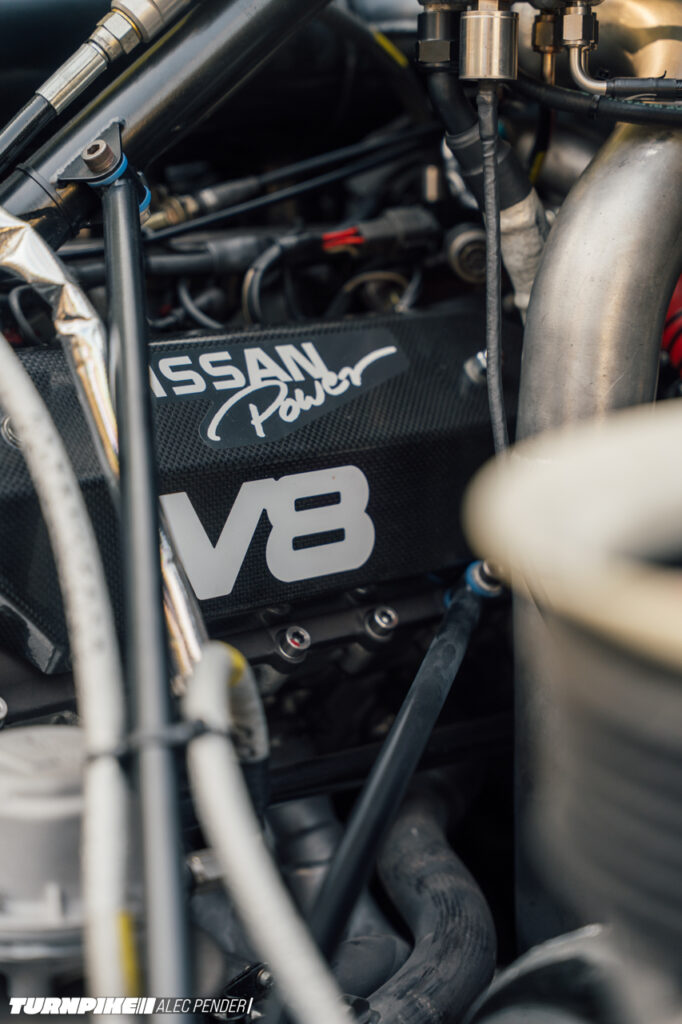

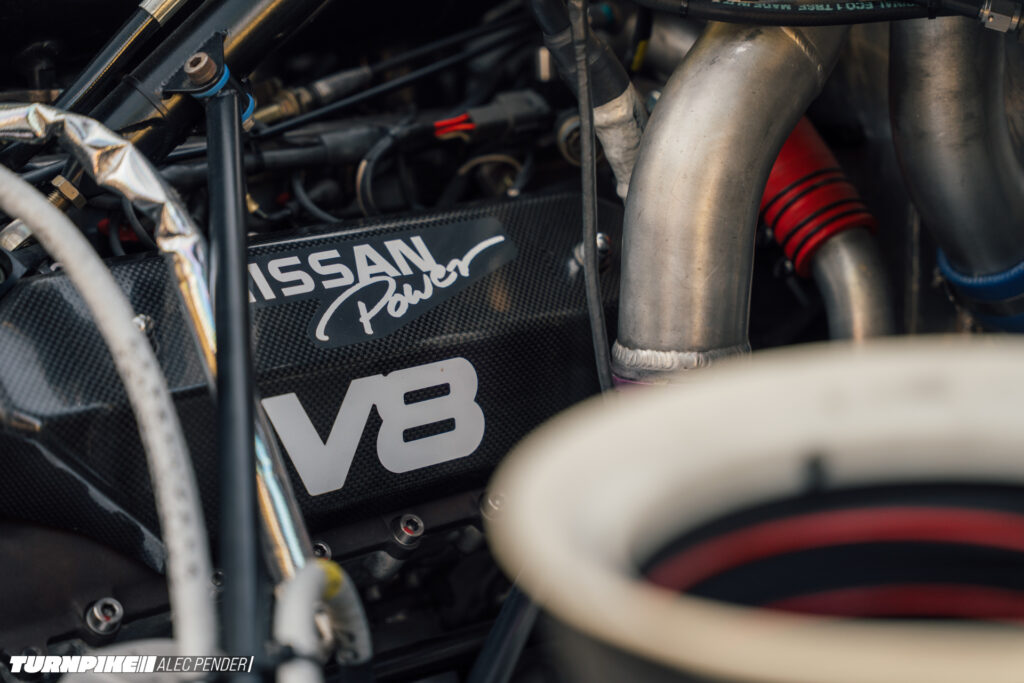

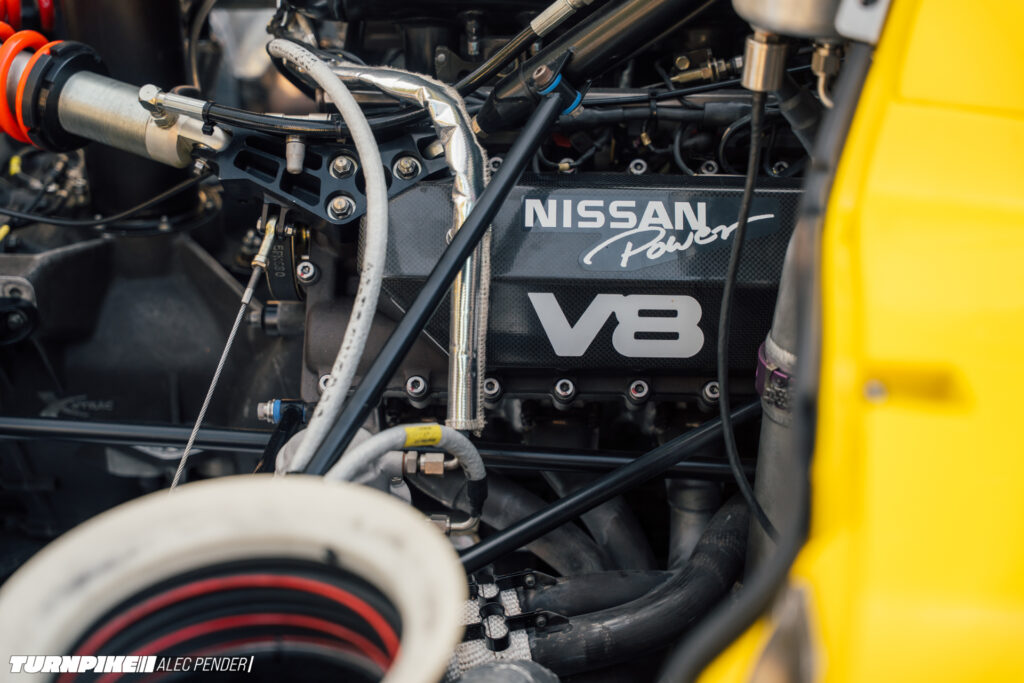

That’s how we’ve ended up standing in Italy, listening to the idle of a 3.5-litre, twin-turbo V8 that once ran down the Mulsanne, now wearing a UK plate. McLaren and Nissan, Erik said, homologated in the UK. Toyota, Porsche and Mercedes in Germany. That’s why this one carries British registration.

The kicker? The car didn’t come back into Comas’ hands until 2019, and even then, it wasn’t just a collect and park moment. It was the beginning of a full restoration and the conversion to street specification.

Comas had the restoration completed between 2019 and 2022. Originally painted in white, only recently did the car become what it is now, wearing full Pennzoil colours, a nod back to his success in the Nissan JGTC R33 and R34.

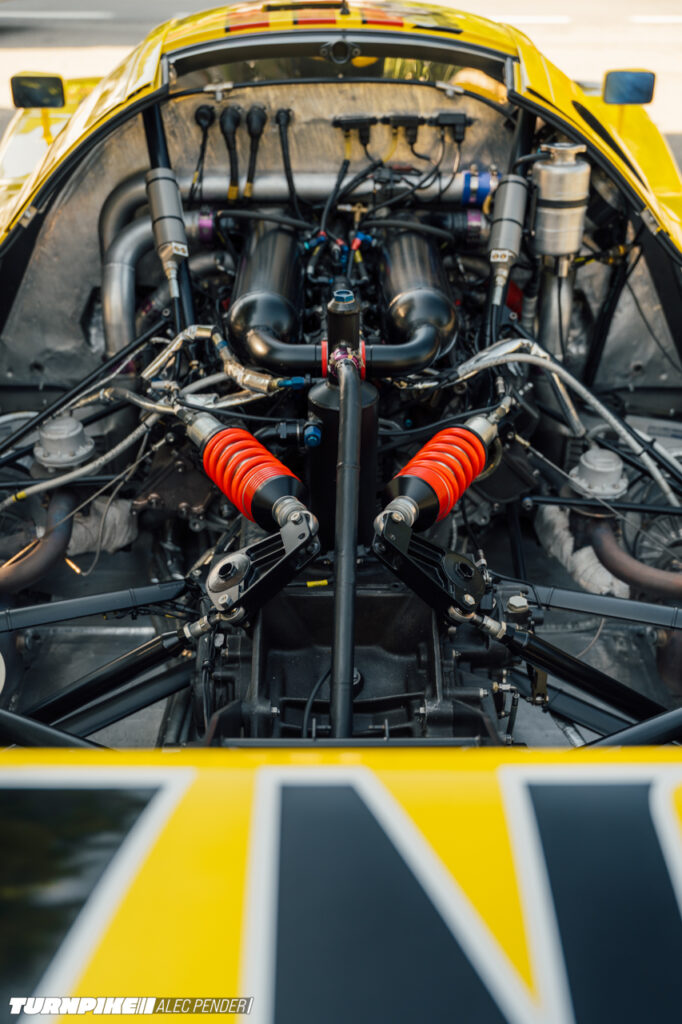

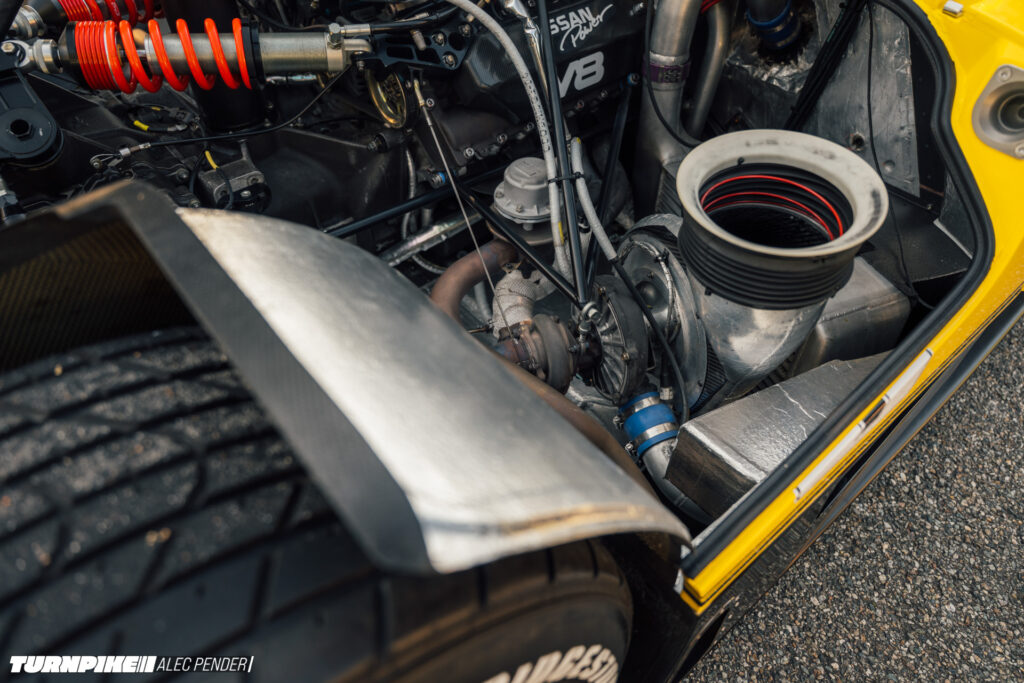

In terms of how much changed from race car to road car, Comas didn’t try to sell us a fantasy. It’s basically the same car. “Very similar to Le Mans, around 95%,” he says. The biggest changes are the ones you’d want, if you plan to drive a GT1 on imperfect public roads.

No more carbon discs. We’re not talking carbon-ceramic, but proper race carbon. They take ages to warm up and would be genuinely dangerous on the street. Steel discs were made, but the calipers remain original.

The springs and dampers are different, with a compromise that keeps it stable on bumps and usable on tight, bumpy mountain roads, while still being enjoyable on track. At Le Mans, the R390 had roughly 6cm of ground clearance, but now it’s around 11–12cm.

It’s still a car that you treat like a live grenade around speed bumps, but now it’s workable. The gearing has been changed; still a six-speed, but with a shortened final drive, as first gear used to top out at around 110km/h. It was perfect for Le Mans but insane on the street.

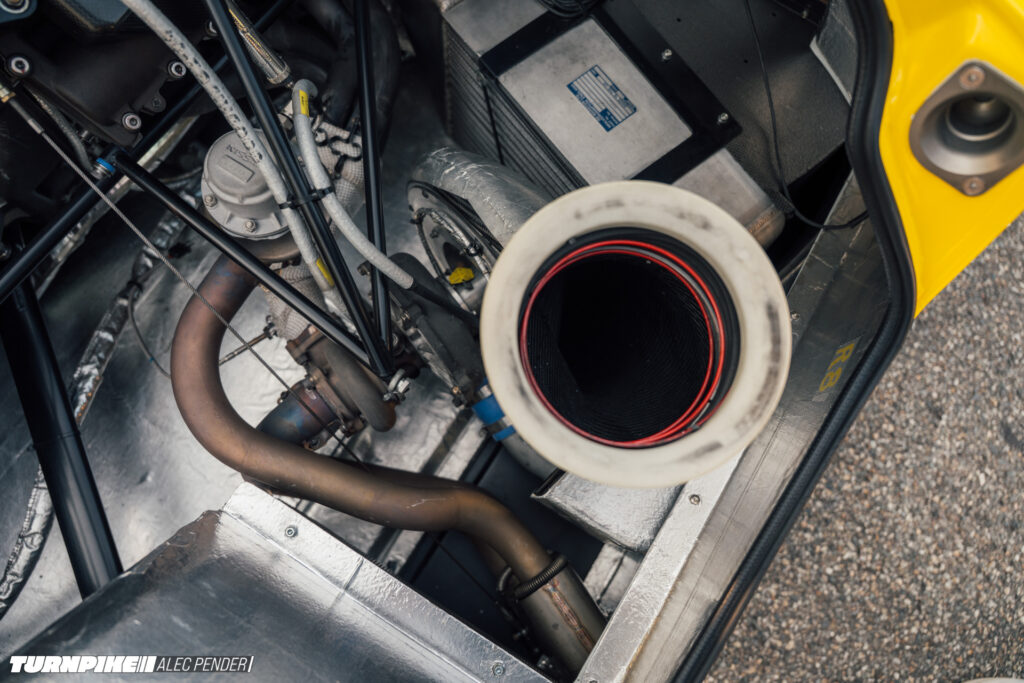

It doesn’t chase an absolute top speed anymore, with V-max now closer to “around 300km/h,” which is still more than enough for any road use. Finally, cooling, with a new radiator built to the original dimensions, plus electric fans and a thermostat so it can survive traffic. Comas has driven it through Monte Carlo, for example, which basically makes this a sensible daily commuter car.

Everything else feels like it was left alone on purpose. There are no added gimmicks, and no modernisation for the sake of convenience. Even the question of a passenger seat was shut down immediately. Sure, with today’s tech you could consolidate electronics into a neat little box, but that’s not the point. Erik wanted authenticity, and in his own words, “The longer you sit with it, a car like this is better enjoyed alone. Like a motorbike. It’s just you and the machine.”

With the rear cover off, the R390 shows its true 90’s race car colours. This is the engine that finished Le Mans, one of the units that helped deliver Nissan a strong 1998 result of third, fifth, sixth, and tenth place finishes – with Comas’ car finishing fifth.

The power from the V8 engine is distributed by an Xtrac sequential transaxle gearbox, and Comas is clear about output. With the mandatory air restrictors in place it made around 600hp. Remove them and it’s basically a Group C racer, with around 1,000hp.

Maintenance needs since the road conversion? Almost none. It was rebuilt as a matter of safety after 25 years, even though the engine was still “good.” Other than that, regular checks, making sure vibrations haven’t loosened anything and keeping an eye on joints and fasteners, but no drama or constant surgery.

Italy is one of the only places where this kind of day feels even remotely possible. Anywhere else, you’d expect sirens and paperwork within minutes. We were joined by Ital Design and its prototype GTR-50, Andrea from Ital Design aligning the stars to make this all happen.

On the move, it’s hard to describe how intense the R390 sounds. It doesn’t just sound loud, it feels loud. There are two exhaust outlets, plus wastegate dump pipes on each side of the car. Comas’ idea of ‘quieter for the road’ is basically a joke. In his own words, “I don’t know the meaning of quiet.”

As we climb into twistier roads, there’s barely enough width for the R390. Yet just watching the car navigate the somewhat bumpy, tight and undulating route, it becomes clear that the car’s street conversion was more than suitable to handle it.

The R390 is special: because it’s rare, because it’s a Le Mans GT1 racer, and because Comas is a living legend, yes. But the real weight of the day comes from the fact that this isn’t a reconstruction or a tribute act.

It’s the actual story coming full circle, the driver who asked for the car in the ’90s, waited decades, and then didn’t just store it. He rebuilt it, kept it authentic, and made it usable, staying true to his dream from 1996.

Massive thanks to Andrea, Italdesign, to Érik and his team, and to everyone who helped this materialise.

What a story and what a car. Really bummed out I missed it at The Ice. That would’ve been a sight!